농민들의 수자원 전쟁 -2장 용수로의 지혜와 서로 협력하는 마을들

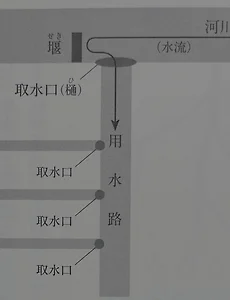

将軍2장 용수로의 지혜와 서로 협력하는 마을들 ●일본 용수로의 특징지금까지 치수에 대해서 기술했는데, 앞에 기술했듯이 치수와 관개가 수레의 두 바퀴가 되어 무논 벼농사를 발전시켜 왔기에 다음은 관개에 대해서 살펴보겠습니다. 메이지 40년(1907) 전국 통계에 의하면, 관개용 수원 중에서는 하천이 65.3%를 차지하여 1위, 저수지가 20.9%로 2위였습니다. 다만, 지역적인 특징이 있어 하천 관개는 동일본에 많고, 사이타마현에서는 82.0%, 니이가타현에서는 74.6%, 이와테현에서는 73.6%를 차지하고 있었습니다. 한편, 저수지는 세토瀬戸 내해 연안의 시코쿠四国・츄우고쿠中国 지방이나 오사카부・나라현 등에 많고, 카가와현에서는 용수원의 67.3%, 나라현에서는 56.7%, 오사카부에서는 46.5%..

2025. 4. 8.

농민들의 수자원 전쟁 -2장 용수로의 지혜와 서로 협력하는 마을들

将軍2장 용수로의 지혜와 서로 협력하는 마을들 ●일본 용수로의 특징지금까지 치수에 대해서 기술했는데, 앞에 기술했듯이 치수와 관개가 수레의 두 바퀴가 되어 무논 벼농사를 발전시켜 왔기에 다음은 관개에 대해서 살펴보겠습니다. 메이지 40년(1907) 전국 통계에 의하면, 관개용 수원 중에서는 하천이 65.3%를 차지하여 1위, 저수지가 20.9%로 2위였습니다. 다만, 지역적인 특징이 있어 하천 관개는 동일본에 많고, 사이타마현에서는 82.0%, 니이가타현에서는 74.6%, 이와테현에서는 73.6%를 차지하고 있었습니다. 한편, 저수지는 세토瀬戸 내해 연안의 시코쿠四国・츄우고쿠中国 지방이나 오사카부・나라현 등에 많고, 카가와현에서는 용수원의 67.3%, 나라현에서는 56.7%, 오사카부에서는 46.5%..

2025. 4. 8.