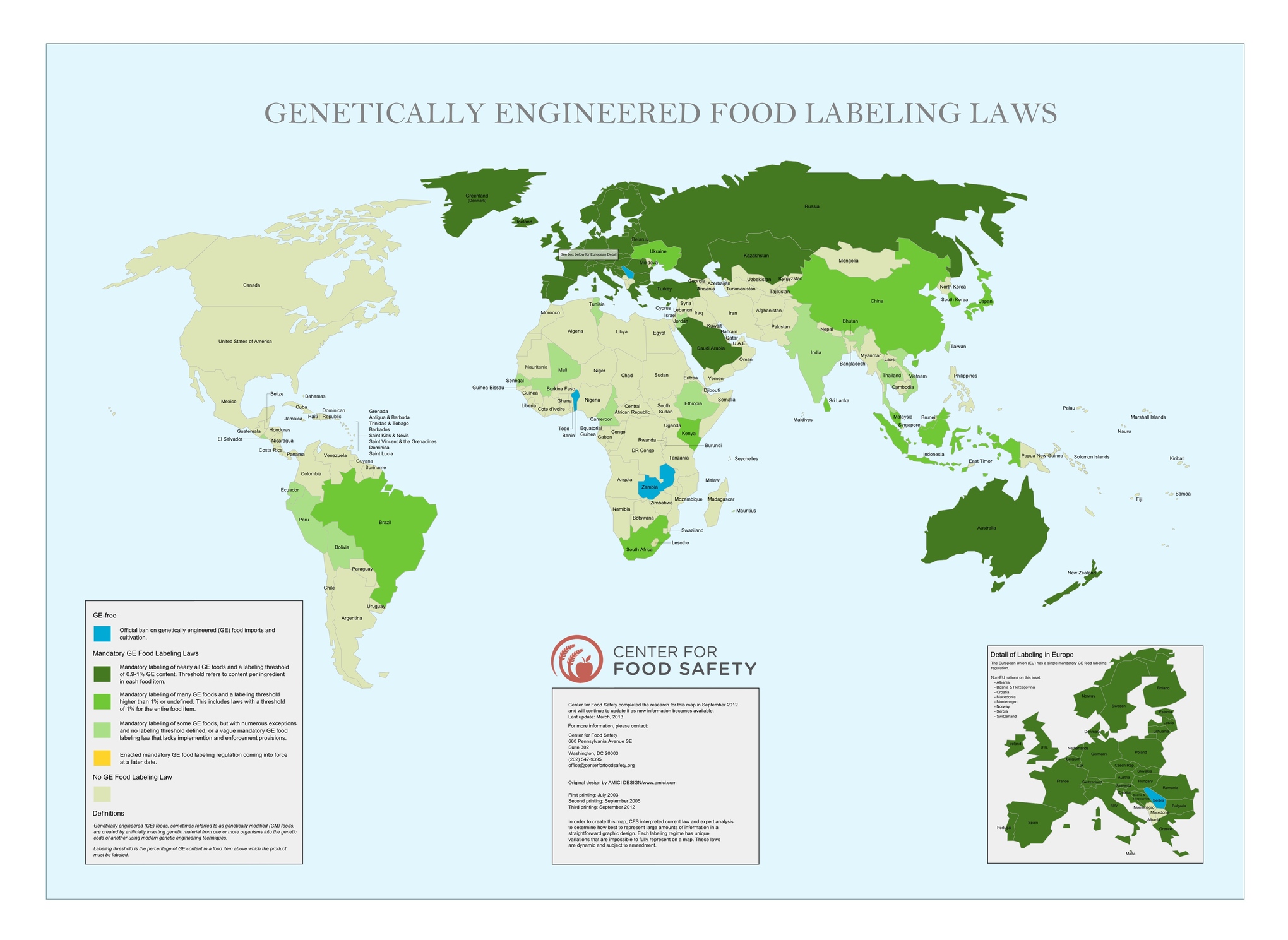

The US Department of Agriculture recently posted new data on how genetically modified crops have taken over American farms in the past decade. It's worth taking a look at some of the highlights:

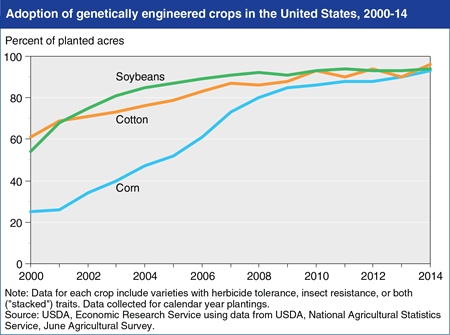

1) More than 93% of corn, soy, and cotton in the US is now genetically modified

US Department of Agriculture

In 2014, GMO crops made up 94 percent of US soybean acreage, 93 percent of all corn planted, and 96 percent of all cotton.

That's a big leap even from the previous year (when the figures were 93 percent of soy, 90 percent of corn, and 90 percent of cotton).

It's also worth adding that 95 percent of sugar beets in the United States are now genetically engineered to be herbicide tolerant — an event that took just three years after they were first introduced in 2008. Roughly 55 percent of US sugar production comes from sugar beets.

(There are a number of other GMO crops in the US — including canola, alfafa, papaya, and squash — but the ones above are the big ones.)

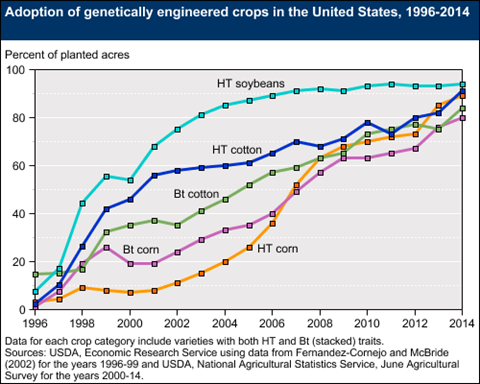

2) Herbicide tolerance and insect tolerance are the most popular traits

US Department of Agriculture

So how did GMOs become so popular? Mainly because of two traits — herbicide tolerance (HT) and insect tolerance (BT):

Herbicide tolerance: Crops that are engineered to be resistant to herbicides have become particularly widespread in the last decade — in part because they make it easier for farmers to kill weeds without damaging crops. (Since 1996, Monsanto has sold both Roundup herbicide and plants that are engineered to be resistant to Roundup.)

The USDA has noted that herbicide-tolerance technology doesn't appear to boost crop yields significantly or increase profitability. But it doesseem to save time and make weed management easier — by, for instance, allowing farmers only to use a single herbicide — which likely explains why it continues to be so popular.

Critics of HT technology argue that this has led farmers to use more herbicides and raises the risk of creating herbicide-resistant weeds. (Some scientists also think that heavy spraying of herbicides has killed off milkweed in the Midwest, leading to the decline of monarch butterfly populations.)

Proponents often retort that farmers are now using a less-toxic herbicide (glyphosate) than they were using before, which is safer for workers — and that herbicide-resistance was a problem with older, conventional crops too. But throughout this debate, herbicide-tolerant crops have continued to soar in popularity in the United States.

Insect tolerance: Meanwhile, the vast majority of US corn and cotton are now engineered to carry a gene from the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), which is toxic to insects and protects the plants from pests.

How useful is this? The Department of Agriculture notes that Bt technology doesn't necessarily increase the maximum yields of plants. But it can help farmers limit their losses to pests — and studies have found that the technology boosts profitability. Bt technology also appears to have led to a reduction in insecticide use over time.

One downside? There's a some evidence that over-planting of Bt corn in some regions is leading to the rise of pesticide-resistant insects.

The USDA notes that use of insect-tolerant crops has fluctuated over time — a lot depends on what pests are prevalent in the United States in a given year. In the early days, Bt corn mostly protected against a moth known as the European corn borer. In recent years, new varieties have been introduced to protect against corn earworm and corn rootworm — and adoption has soared. Meanwhile, insects haven't yet posed a major problem for soybeans, so there's not a lot of demand for Bt soy, at least so far.

(The other big GMO crops being commercially grown in the United States are herbicide-tolerant canola, herbicide-tolerant sugar beets, herbicide-tolerant alfalfa, virus-resistant papaya, and virus-resistant squash.)

3) Up to 70% of processed foods in the US now contain GMO ingredients

(Scott Olson/Getty Images)

There are a few other GMO crops in the United States — particularly canola, alfafa, papaya, and squash — but corn, soy, and sugar beets are the big ones.

As a result, an estimated 60 to 70 percent of processed foods in US grocery stores contain at least some GMO ingredients like high-fructose corn syrup or soy lecithin. About half the sugar consumed in the United States is also GMO. on top of that, companies have used genetic engineering to create certain enzymes and hormones for cheese and milk production.

The fact that genetically engineered corn and soy are so widespread has also made it difficult for companies to avoid them. Annie Gasparro of The Wall Street Journal recently wrote about how Ben & Jerry's was trying to avoid GMOs entirely in response to consumer pressure. one problem? The vast majority of feed for dairy cows in the United States is made with GMO corn, soy, or alfafa — so the company is having a hard time finding "GMO-free" milk.

(By the way, it's worth reiterating that there's no good scientific evidence that GMO crops are particularly harmful to your health, although they remain unpopular in many corners for a variety of reasons.)

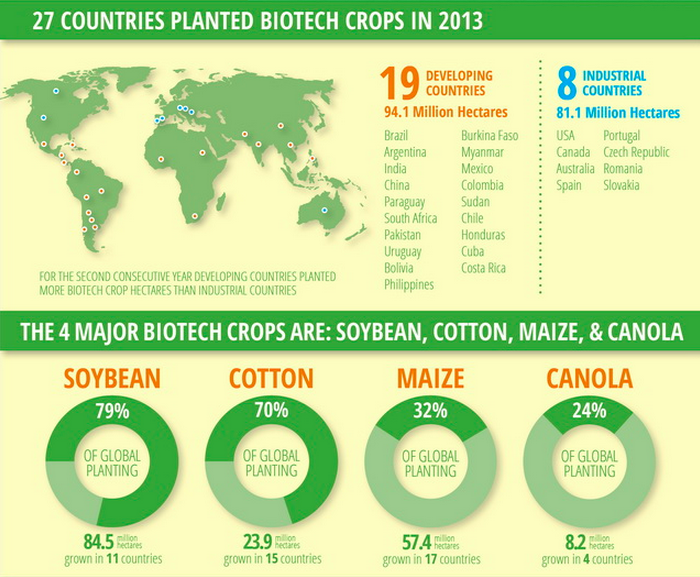

4) Worldwide, about 12% of farmland is devoted to GMOs

International Service for the Acquisition of of Agri-Biotech Applications

The Department of Agriculture doesn't keep tabs on genetically modified crops grown worldwide, but the International Service for the Acquisition of of Agri-Biotech Applications does.

Globally, GMOs were planted on 175 million hectares in 2013 — or roughly 12 percent of global farmland. That's up one-hundred-fold from two decades ago. And GM crops are now planted in 27 countries.

5) But GM crop growth may be slowing

The map above is a little simplistic, however. The vast majority of GM crops are grown in just five countries: the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, and India. And as the chart below from Nature shows, growth seems to be slowing:

(Nature)

One reason is saturation. Virtually all corn and soy and cotton in the United States is now genetically engineered.

-------

(For the pointer to the USDA report, thanks to Kay McDonald at Big Picture Agriculture.)

'庫間 > 해외자료' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 무경운 농법으로 가뭄을 이기자 (0) | 2014.08.27 |

|---|---|

| 토종 감자 축제 (0) | 2014.08.21 |

| 유기농산물이 좋다는 연구결과 (0) | 2014.07.12 |

| 아프리카와 중국의 농업동맹 (0) | 2014.07.04 |

| 미국의 다이어트가 실패한 이유 (0) | 2014.07.04 |