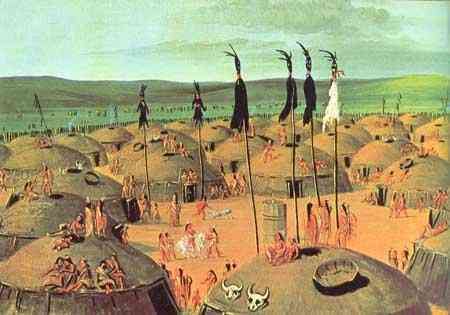

The common stereotype of American Indians paints a picture of them as horse-mounted, nomadic, buffalo hunters. This stereotype is often based upon the Northern Plains Indians which the American traders, missionaries, and military encountered in the nineteenth century. However, not all of the Indian nations of the Northern Plains were buffalo hunting nomads: the tribes of the upper Missouri River Valley—the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara—were sedentary agriculturalists. These villages raised corn, beans, sunflowers, tobacco, pumpkins, and squash. They produced not only enough agricultural products for their own use, but also a substantial surplus which was traded to other tribes, and later to the Europeans and Americans. Their agricultural surplus brought them wealth and political power.

Agricultural Fields:

Sensitive to the ecological demands of the Northern Plains, fields were established in the fertile bottomlands where the tillable soil was renewed annually by flooding. The brush which was cleared for the planting was spread over the fields and burned. This practice softened the soil and added nutrients. Hidatsa elder Buffalo Bird Woman, speaking about 1910, says:

“It was well known in my tribe that burning over new ground left the soil soft and easy to work, and for this reason we thought it a wise thing to do.”In addition, fields were taken out of production and allowed to lay fallow for two years in order to let the land rejuvenate.

Among the Arikara, each family worked a plot of land from a half acre to an acre and a half in size. The plots were separated from each other by brush and pole fences. These fields tended to be irregular in shape. Among all of the tribes, the fields were tended by the women. Since no fertilizer was used, the fields were periodically abandoned and new fields were cleared and put into use.

In preparing the fields for planting, the Mandan used rakes and digging sticks. Some of the rakes were made from deer antler and some were made from long willow shoots. In cultivating the fields, the Mandan used a hoe that was often made from the shoulder-blade of the buffalo or elk, which was attached to a long wooden handle.

Among the Mandan, there were watch platforms scattered throughout the fields. These platforms were staffed by young boys who kept a careful eye out for enemy warriors who might threaten the unprotected women who were working in the fields.

Crops:

Sunflowers – black, white, red, sand striped – were the first crop planted in the spring and they were the last crop harvested in the fall. The sunflowers were planted around the edges of the field. The Hidatsa name for April is Mapi’-o’ce-mi’di which means Sunflower Planting Moon.

Sunflower seeds were parched in a clay pot and then made into meal. Some of this meal was used to make sunflower balls which were an important item in the diet. Warriors would carry a sunflower-seed ball wrapped in a piece of buffalo-heart skin. When tired, the warrior would then nibble at the ball. Hidatsa elder Buffalo Bird Woman describes the effects of nibbling on a sunflower-seed ball:

“If the warrior was weary, he began to feel fresh again; if sleepy, he grew wakeful.”Corn planting began after the sunflower seeds were planted. When the gooseberry bush began to leaf it was time to plant. Corn was planted in hilled rows with the hills about four feet apart. This spacing was tuned to the local rainfall. Closer spacing would bring higher yields only if the growing season were unusually wet. A second planting of corn was done when the June berries were ripe.

Most families kept enough seed corn for two years. After two years the corn would not come up well and after four years the corn seed was dead and worthless.

The village tribes of the northeastern Plains planted between nine and eleven different varieties of corn. The Indians also observed some basic plant genetics. According to Hidatsa elder Buffalo Bird Woman:

“We Indians knew that corn can travel, as we say; thus, if the seed planted in one field is of white corn, and that in an adjoining field is of some variety corn, the white will travel to the yellow corn field, and the yellow to the white corn field.”The corn grown by the Missouri River tribes was extremely hardy. It adapted itself to varying amounts of moisture and produced some crop under drought conditions. It was also resistant to the unseasonable frosts which are apt to occur in the region.

One of the main varieties of corn was flint corn, which was well-adapted to the semi-arid Northern Plains climate. This corn took about 60 days to mature and, because of its short stalk, was able to withstand winds fairly well. This corn is usually eight rowed, occasionally ten or twelve rowed. It is high in protein and the grain is very hard and heavy.

The tribes also grew flour corn which is softer and lighter. It is largely composed of starch and is deficient in protein. The advantage of this species of corn, however, was that it could be easily crushed or ground and it was much softer than the flint corn when eaten parched.

The farming efforts of the village tribes on the northeastern plains produced surplus crops which were used in developing trade with other tribes and, later, with the European immigrants. The Sioux, for example, would make yearly trips to the Arikara villages to trade buffalo robes, skins, and meat for corn. During the 19th century, the Arikara produced 2,000 to 3,000 bushels of corn annually. Even when drought and early frost killed part of their crop, they had surplus to trade.

Squash was planted in late May or early June. To prepare the seeds for planting, they were first wetted, then placed on matted red-grass leaves and mixed with broad-leaved sage. Buffalo skin was then folded over the squash bundle and it was then hung in the lodge to dry for two days. During this time the seeds would begin to sprout. The sprouted seeds were then planted in hills about four feet apart.

Immediately after planting the squash, the beans were planted in hills about two feet apart. The beans were often planted between the rows of corn. Five different varieties of beans were planted.

Tobacco was also raised by the tribes. Among the Hidatsa, tobacco was planted only by old men. According to Hidatsa elder Buffalo Bird Woman, young men did not smoke as

“they were taught that smoking would injure their lungs and make them short winded so that they would be poor runners. But when a man got to be about sixty years of age we thought it right for him to smoke as much as he liked.”The Hidatsa tobacco fields were about 18 feet by 21 feet.

Storage and food preparation:

The village tribes stored their crops for winter in cache pits. These pits were shaped like a jug with a narrow neck at the top. Among the Mandan, the storage pits would be from 6 to 8 feet deep. The cache would hold 20 to 30 bushels. They were lined with grass or woven plants to prevent spoilage from moisture.

In preparing the corn for storage the ears would be braided into strands. The length of the braids was standardized: the length was from knee down around the foot and up to the knee again. once braided, the corn would be hung on the frame of the drying scaffold.

One of the popular ways of preparing the corn for eating was making corn balls. In one version of the corn balls, pounded sugar corn was mixed with grease. Another kind of corn ball was made using pounded corn, pounded sunflower seed, and boiled beans. It is reported that this tasted like peanut butter.

http://www.dailykos.com/story/2012/04/03/1080228/-Indians-101-Northern-Plains-Agriculture-

'庫間 > 해외자료' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 담배와 유기농 농약 (0) | 2012.04.09 |

|---|---|

| 유기농업이 세계를 먹여살릴 수 있는 6가지 이유 (0) | 2012.04.09 |

| 다락논에서 토착지식을 강화하기 (0) | 2012.04.08 |

| 거름 자급이 당신이 할 수 있는 가장 생태적인 일인 이유 5가지 (0) | 2012.04.06 |

| 화학비료 사용은 대기에 아산화질소를 증가시킨다 (0) | 2012.04.06 |