Agrobiodiversity, or agricultural biodiversity, includes all the components of biological diversity of relevance to food and agriculture, as well as the components of biological diversity that constitute the agro ecosystem: the variety and variability of animals, plants and micro organisms, at the genetic, species and ecosystem levels, which sustain the functions, structure and processes of the agro ecosystem. Indigenous and traditional agricultural communities throughout the world depend on, and are custodians of, agrobiodiversity maintained within agricultural landscapes through various forms of traditional resource management. These communities are coping with an increasing number of interlocking stresses that result from different aspects of global change, including the problems related to population increase, insecure and changing land ownership, environmental degradation, market failures and market globalization, and protectionist and inappropriate policy regimes and climate change (Morton, 2007). Climate change presents a major concern, often interacting with or exacerbating existing problems. It makes new demands for adaptation and coping strategies, and presents new challenges for the management of the environment and agro ecosystems. Discussions on global policies related to climate change have largely disregarded the potentially negative effects of many of the proposed policies on indigenous and traditional agricultural communities and their livelihoods and rights. Agrobiodiversity has also been largely overlooked in discussions on climate change, despite its importance for the livelihoods of rural communities throughout the world and for the development of adequate adaptation and mitigation strategies for agriculture. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report (Adger et al., 2007) ignores the role of diversity in production systems and the central role that agrobiodiversity will have to play in both adaptation and mitigation at the country, landscape, community and farmer levels. Indigenous and traditional agricultural communities are adapting to change and are developing ways of strengthening the resilience of agricultural landscapes through various local strategies based on the protection of traditional knowledge and agrobiodiversity. The approaches being adopted include the use of centuries old traditional practices (e.g. the forest management of indigenous Hani people of Yunnan province in China, and 3000 year old Cajete terraces and the associated agricultural system in Mexico) and their adaptation to changing conditions, as well as the development and adoption of new approaches. Over the past two years the Platform for Agrobiodiversity Research has been collecting information on the ways in which indigenous peoples and rural communities have been using agrobiodiversity to help cope with climate change. The information comes from over 200 different stories, reports and articles from many different sources . Here we present an analysis of the information and identify the most important adaptation strategies adopted. We also set out some of the ways in which agrobiodiversity can be used to help improve the adaptability and resilience of the farming systems managed by rural communities and indigenous peoples around the world. A conceptual framework was designed to enable the review of a wide range of community devised strategies employed in agricultural ecosystems and landscapes in different environments (mountains, drylands, forests, wetlands and coastal regions). The results of the review elucidate the intrinsic link between adaptation and the protection of ecosystem, agrobiodiversity and traditional knowledge.

UNDERSTANDING ADAPTATION

Together with increasing temperatures, climate change also leads to increasingly unpredictable and variable rainfall (both in amount and timing), changing seasonal patterns and an increasing frequency of extreme weather events, floods, droughts and .re. These can result in decreasing productivity, changing agro-ecological conditions, increasing or altered patterns of pest activity and accelerating rates of water depletion and soil erosion. The changes, and the responses of communities to them, are many and varied in both nature and extent, depending on situation, culture, environment (mountains, drylands, forests, wetlands, coastal), agro-ecosystem, environment and opportunities. In order to understand and analyse the information an appropriate conceptual framework was needed.

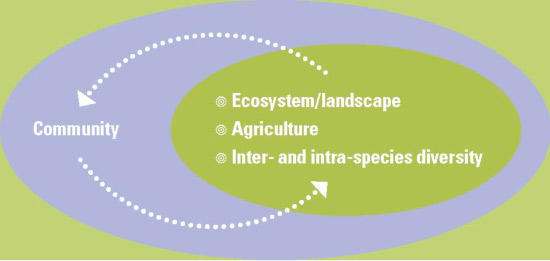

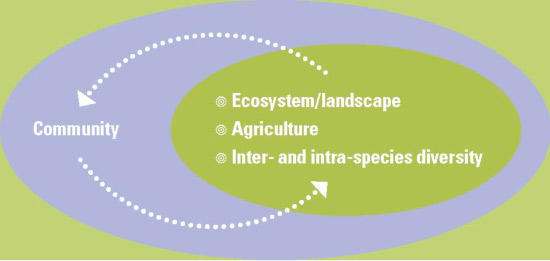

The impacts of climate change are felt at the level of the natural resource base upon which rural communities depend, at the farming system level, and at the level of individual species (Vershot et al., 2005). At each level, communities employ a different set of actions to enhance the resilience of local food systems. This grouping of activities into the ecosystem or landscape level, the farm level, and the species level provides a basis for the development of a conceptual framework for helping to understand how communities use agrobiodiversity and ecosystem services to adapt to climate change.

Indigenous and traditional agricultural communities develop their local food systems at the ecosystem or landscape level (or the system level) by managing ecological and biological processes within the system. In this way, they construct niches, shape microclimates, encourage landscape regeneration and influence gene flow. These management activities are often regulated by social institutions, customary laws and cultural values, which encompass traditional agro-ecological knowledge. Based on the feedback from the environment, the management practices are adjusted in a way that supports the maintenance of the ecosystem, helps maintain agrobiodiversity and enhances resilience to climate change (Salick and Byg, 2007). This type of adaptive management is perhaps best understood by using a whole system approach, in which the adaptability and resilience of the system and its components are determined by actions at different levels and interactions within the system, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The system can be an ecosystem, for example a watershed, or an agricultural landscape spreading across ecosystems, for example an agricultural landscape consisting of terrestrial and aquatic components.

Some studies refer to the whole ‘socio-ecological’ system as a way of including the concept of adaptation in environments in which humans are involved. Socioecological systems behave as complex adaptive systems, in which the humans are integral components of the system seeking to decrease vulnerability and increase resilience of the system through different management strategies (Walker et al., 2004). The vulnerability of such systems relates to the exposure and sensitivity to perturbation and external stresses, and the capacity to adapt (Adger, 2006). In these systems, resilience can be described as the capacity of a system to absorb recurrent disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change without losing its function, structure, identity and feedback (Walker et al., 2004). The ability of the humans to influence the resilience of the system is referred to as their adaptive capacity (or adaptability). The material within the agro-ecosystem, including species complexes, soil biota and traditional varieties, can also possess greater or lesser adaptability and capacity to evolve and change in the face of changes in temperature, rainfall or other environmental changes.

Figure 1 -Resilience is enhanced through the activities at and between different levels within a system.

Here we use this system-based approach to identify (i) the main adaptation strategies at the levels of the ecosystem, the agricultural system, and inter- and intra-species diversity, and (ii) interactions between the levels that contribute to the resilience of a system. A special focus is put on the social and community dimensions of adaptation discussed in the sections following the results of the analysis. The main patterns and approaches that emerge are illustrated with specific examples taken from the cases studied.

ADAPTATION STRATEGIES

ECOSYSTEM OR LANDSCAPE-BASED APPROACHES

At the ecosystem or landscape level, adaptation activities can reduce the impacts of climate change and buffer their effects, reducing the negative impacts on humans and the environment. A variety of projects have been undertaken to protect and restore ecosystems, rehabilitate degraded landscapes and sustainably manage natural resources. These strategies appear to reduce vulnerability and strengthen resilience of local food systems to floods, droughts, rising sea level and extreme weather events. Examples from forest and mountain ecosystems, coastal areas, drylands and wetlands are given in the following paragraphs.

In Nicaragua, Honduras and El Salvador, where climate change has exacerbated soil erosion and watershed degradation, a forest landscape restoration project has been undertaken. This aimed to increase the resilience of tropical hillside communities by halting deforestation, restoring watersheds, diversifying production systems and encouraging sustainable landscape management (IISD, 2003a). In the Philippines, the Camalandaan Agroforest Farmers Association, a community-based land and resource management organization, have undertaken tree planting and forest protection to reduce sudden onrushes of water (during the rainy season) and depletion of water reserves (during the dry season) (Equator Initiative, 2008b).

In the coastal regions of Asia and Africa, community-based mangrove restoration has been undertaken in Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Kenya, Senegal and Zanzibar. Mangroves function as a protection against storms and can help to mitigate salt water intrusion, coastal erosion and floods.

Restoration of watersheds is helping to reduce vulnerability to climate change-associated stresses in a number of regions. In the drought-prone regions of Maharashtra in India, rehabilitation of a watershed ecosystem conducted on a micro-catchment basis helped to improve soil conditions, increase water availability, regenerate landscape and diversify agricultural production through a number of activities, including water harvesting and the encouragement of natural regeneration (IISD, 2003b).

In many cases, sustainable management practices have been revived and implemented to reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience. In Sudan, a community-based rangeland rehabilitation project aimed at increasing resilience to drought by improving soil productivity through sustainable land management, diversification of production systems, agroforestry and sand dune fixation (IISD, 2003b). In Tibet, pastoralists have engaged in the restoration of peatlands (Wetlands International, 2009). Thousands of hectares have been restored by regulating grazing pressure and erosion. It is believed that this will regulate the .ow of the Yellow and Yangtze rivers, thereby reducing flooding and drought risks for the communities downstream.

IMPROVING THE RESILIENCE OF AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS

At the level of the agricultural system, adaptation strategies include integration of trees and livestock into production systems; cultivation of a higher diversity of crops (diversification); and improved crop, water and soil management. These are not usually carried out singly but are combined in different ways depending on the ecology, needs of communities, availability of different materials and the challenges faced. Most adaptation initiatives include the use of approaches based on agroforestry and crop diversification, which are often combined with improved crop, soil (including soil biota and nutrients) and water management. Adaptation activities include both the revival of traditional production practices and the adoption and development of new techniques (e.g. a switch to low input agriculture and the use of alternative ways of livestock management). Some examples follow.

Agroforestry

Agroforestry is an increasingly important adaptation strategy for enhancing resilience to adverse impacts of rainfall variability, shifting weather patterns, reduced water availability and soil erosion. In Burkina Faso, to fight desertification and rehabilitate degraded land, trees are planted in the fields and around villages with a traditional water harvesting and soil improvement technique known as zaï. This technique, in combination with crop diversification and other techniques, through innovation and experimentation, has resulted in the development of an integrated agro-sylvo-pastoral system with higher resilience to droughts (Taonda et al., 2001).

Home gardens and other diversity-rich approaches

A number of adaptation case studies emphasize the importance of diverse home gardens in ensuring the family food supply in areas significantly affected by climate change. Examples from Bangladesh describe two types of adaptation strategies for enhancing the resilience of home gardens. In drought-prone regions, the resilience of traditional homestead gardens is strengthened through intercropping of fruit trees with vegetables, small-scale irrigation and organic fertilizers (FAO, 2010a). In the flood-affected regions, floating gardens have been created for cultivation of a mix of traditional crops, including saline-tolerant vegetables such as bitter gourd, red amaranth and kohlrabi. The floating gardens, in combination with alternative farming methods such as duck rearing and fishing, are important source of food during floods (Haq et al., 2009).

Crop, soil and water management

In arid and semi-arid regions, and increasingly in the sub-tropics and the tropics, soil productivity and water availability have decreased due to a combination of climatic and non-climatic factors such as ecosystem degradation and over-exploitation. Improved management of soil and water within cropping systems has helped communities to cope with these problems. In a number of adaptation projects, traditional soil and water management practices involving diversified cropping have been revived. Traditional knowledge is often combined with innovation resulting in better crop, soil, and water management practices. The most common methods for the improvement of soil productivity and water availability are a combination of: minimum soil disturbance, direct seeding or planting, live or residue mulching, cover crops with deeper rooting crops including annual and perennial legumes, micro-catchment water harvesting (e.g. infiltration pits and planting basins) and re-vegetation. These are key elements of practices that have become known as Conservation Agriculture in which ecosystem services are enhanced within the production systems at the farm and landscape level.

In Burkina Faso, to rehabilitate the soil, farmers apply mulch to degraded land, which attracts termites. The termites open burrows through the sealed surface of the soil and slowly improve soil structure and water infiltration and drainage (Ouédrago et al., 2008). In Sri Lanka, saline lands are brought back into production with green manure. Green manures are grown in situ (sunn hemp, green gram, black gram and grasses) or green leaf manure is obtained from trees and bushes around the fields (Vakeesan et al., 2008). In Jamaica, guinea grass mulching is a local strategy adopted in the low-rainfall areas to control soil erosion, increase the water retention capacity of the soil and improve soil structure (FAO, 2010b).

Traditional rainwater harvesting and irrigation systems have been revived and play an important role in augmenting the water supply in water stress-prone environments. In Tunisia, there is an increasing interest in jessour, a traditional system of dams and terraces for collecting run-off water, which enables cultivation of olives, fruit trees, grains and legumes (Reij et al., 2002). In the Andes, the Quechua have revived the waru waru, an ancient cultivation, irrigation and drainage system for increasing the productivity of land with high salinity levels and poor drainage in areas with frequent droughts and frost (Ho, 2002). The waru waru regulate microclimate, soil moisture and pest activity.

Organic agriculture

Farmers’ experiences show that organic agricultural practices, both traditional and innovative, can strengthen the resilience of local food systems. Reports on the importance of organic agriculture come from India, Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Nepal, Honduras, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Nicaragua, Cuba and the Philippines. In Rajasthan, India, an increasing number of small-farmers are adopting vermicomposting – a non-traditional method of improving the nutrient content and water-holding capacity of the soil. This method is combined with cultivation of stress-tolerant crops, crop diversification, green manuring and mulching (Shah and Ameta, 2008). In Nepal, farmers use traditional and non-traditional organic agricultural practices to improve water use efficiency, prevent erosion and improve the productivity of cropping systems (Ulsrud et al., 2008).

Traditional food systems

In traditional food systems a number of methods are used to maintain soil productivity

(e.g. intercropping, crop rotation, fallowing). These practices continue to ensure food and livelihood security under increasing climate change and variability. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change database of local coping strategies includes the following examples of traditional agricultural practices (UNFCCC, 2010).

- In Tanzania, the Matengo living in the highlands have cultivated steep slope fields for more than a century using a grass-fallow-tied ridge system to grow maize, beans, wheat and sweetpotatoes, all on a rotational basis with a fallow period.

- In Indonesia, the Kasepuhan of West Java optimally utilise their natural resources through an integrated fish-rice system. Fish-rice farming systems are also used in a number of other Asian countries such as Bangladesh.

- In Goa, India, the Khazans’ agriculture-aquaculture system, based on the principle of a tidal clock and salinity regulation, ensure sustainable management of resources. on the Indian Andaman and Nicobar Islands farmers cope with the extreme heat and dryness of summer through a number of techniques, including mulching and intercropping of coconut and betel nut seedlings with banana plants.

- In Bhutan, in periods of food scarcity due to extended dry seasons and infestation by pests and diseases, subsistence farmers rely on wild foods. The farmers cultivate crops, rear livestock, and manage common pool resources such as communal grazing land and communal forests for leaf litter and forest-based food products (wild tubers, fruits, vegetables, medicines etc). In times of crop failure due to delayed or weak monsoon and pests, livestock and wild foods meet the household nutritional requirements.

Pastoralism

Pastoralists in the Sahel, by breeding their herds over many generations in often harsh and variable environmental conditions, developed many different breeds with valuable traits. Traditional pasture and herd management systems include the conservation of natural ecosystems through extensive ranching and rotational grazing, and keeping a mixture of cattle, goats and sheep (Morton, 2007). Due to the effects of climate change, mainly the more frequent occurrence of drought; species and breeds with adaptive traits are becoming increasingly important. In the Ethiopian Borana rangelands, pastoralists have retained their nomadic ways but are replacing their cattle herds with camels, which feed on trees as well as grasses and can survive longer periods without water (New Agriculturalist, 2009a).

Pollinators

During the past few years apple production in Himachal Pradesh, India has been continually declining. A study has shown that this decline in productivity is due to pollination failure (Pratap, 2008). The reasons are lack of trees that can provide fertile compatible pollen and lack of pollinators (bees, butter.ies and moths). To overcome the lack of insect pollinators farmers are renting honeybees, decreasing the numbers of pesticide sprays and carrying out hand pollination (Pratap, 2008).

THE USE OF INTER- AND INTRA-SPECIES DIVERSITY

Maintenance of high levels of inter- and intra-species diversity is a strategy to decrease vulnerability and enhance resilience to climate change and associated stresses. Adaptation activities include the maintenance and reintroduction of traditional varieties, the adoption of new species and varieties to meet newly developed production niches, and the development of ways of ensuring that materials remain available (e.g. community seed banks) and adapted (e.g. participatory plant breeding). Linked to the developed of adapted and adaptable materials have been adjustments in cropping patterns and crop cycle.

As a result of climate change, indigenous and local crops and varieties, particularly drought-, salt- and flood-tolerant, fast-maturing and early- or late-sowing crops and varieties, are increasingly cultivated. Their availability is improved though the establishment of community seed banks. Reports from drought-prone regions of Zimbabwe, India, Nicaragua, Kenya, Vietnam, the Philippines, Mali, the Timor Islands and other countries show an increasing importance of drought-tolerant crop varieties of millet, sorghum and rice. The reports also mention other drought-tolerant species and varieties of cereals, fruit and vegetables as well as wild species. In Botswana and Namibia, drought-tolerant wild fruit tree species (e.g. Sclerocarya birrea, local name: morula; Azanza garckeana, local name morojwa) are planted around the villages with the aim of domesticating them (Bonifacio and Zanini, 1999). In the areas experiencing an increased level of flooding and salinization of freshwater and agricultural land; salt- and flood-tolerant crops and varieties have been introduced. In India, community seed banks with a focus on rice have been established to strengthen the community seed supply of flood-resistant varieties in Bihar and Bengal and saline-resistant varieties in Orissa (Navdanya, 2009).

Several reports indicate a switch to short-duration varieties and adjustments in planting and harvesting dates as a response to a decreasing length of growing season and changes in seasonal patterns of precipitation and temperature. In India, in areas where crops had failed due to heavy rainfall during the pod formation stage, farmers have switched to short-duration varieties and adjusted sowing depth and date (unpublished data). In Cambodia, there is a shift in the planting date of rice; rice seedlings are planted in November instead of in September (Mitin, 2009). In Ghana, farmers are planting early maturing crops and sowing the seeds earlier than in previous years (Mapfumo et al., 2008).

In Uttar Pradesh, in the foothills of the Himalayas, communities are experiencing an increasing frequency of flash floods; dry spells during floods; changes in flood timing (longer, delayed or early); increased duration and area of waterlogging; and changes in time, volume, and pattern of rainfall. Adaptation to climate change required the development of a new crop calendar as illustrated below (Wajih, 2008). Crops that are fast-maturing, flood-tolerant and with soil-rehabilitating characteristics are planted according to the calendar.

Adapted from Wajih, 2008

The selection of new varieties by farmers and participatory plant breeding (PPB) are supporting adaptation to changing production environments. Often, adaptation and selection of traditional varieties is associated with on-farm conservation activities. In Bangladesh, the development of short-duration rice varieties formed part of the adaptation strategies of people living in the Gaibandha district of the Char islands, where there has been an increase in the land area affected by major floods from 35% in 1974 to 68% in 1998. on Timor Island, to strengthen the resilience of agriculture to erratic rainfall, farmers have developed their own varieties of maize, sorghum, foxtail millet, dryland rice and cassava (Kieft, 2001).

In Nepal, changes in the monsoon pattern have caused a disruption to rain-fed agricultural systems and exacerbated genetic erosion of local landraces with drought-resistant and lodging-tolerant characteristics. Farmers have responded by establishing a seed bank and engaging in a PPB programme. A total of 69 rice varieties have been revived and stored at the seed bank (Ulsrud et al., 2008).

In Honduras, farmers organized community-based agricultural research teams, to diversify their plant genetic resources and develop hardier plant varieties that grow well on their soils. Responding to the higher occurrence of hurricanes, farmers were able to produce improved maize varieties through a participatory breeding process that are shorter and capable of withstanding the physical trauma brought by the hurricanes, with a higher yield and yet are still adapted to high-altitude conditions. The selection process was accompanied by a conservation effort, as the seeds of the selected species are stored in a community seed bank, assuring availability of healthy and resistant plants (USC Canada, 2008).

In several countries the System of Rice Intensification (SRI), a different rice agronomy that also works well with traditional varieties, is spreading and already raising productivity and income of more than 1 million small indigenous and traditional farmers around the world on over 1 million hectares. SRI benefits derive from changes in the ways that their existing resources are used through a set of modified agronomic practices for managing rice plants and the soil, water and nutrients that support their growth.

Some of the main adaptation strategies at different levels

Ecosystem or landscape

Activities at the ecosystem and landscape level aim to mitigate and buffer the effects of climate change through ecosystem protection and restoration, landscape rehabilitation and the sustainable use of natural resources. Examples are:

- Reforestation of tropical hillsides, riparian forests and mangroves.

- Rangeland rehabilitation and improved pasture management.

- Restoration of wetlands, peatlands, watersheds and coral reefs.

- Re-vegetation in drylands.

Agricultural systems

At the agricultural system level, the resilience of local food systems is enhanced through the diversification and sustainable management of water and soil. Commonly employed strategies are:

- Diversification of agricultural landscapes (agroforestry).

- Diversification of production systems (cultivation of a higher diversity of crops and varieties and crop-livestock-trees integration.

- Low-input agriculture, soil conservation and improved water management and use efficiency (mulching, cover crops, rainwater harvesting, re-vegetation, fallow, intercropping, crop rotation).

- Adjustments in crop and herd management (changes in crop cycle).

Intra- and inter-species diversity

Intra- and inter-species diversity is protected, used and redistributed to strengthen the resilience of agricultural systems and maintain production in stress-prone environments. The main adaptation measures are:

- Use of stress-tolerant and fast-maturing crop species and varieties; and stress-tolerant species and breeds of cattle.

- Protection, reintroduction and distribution of traditional crops through community seed banks and on-farm conservation.

- Stress tolerance improvement through farmers’ selection and participatory plant breeding.

A WHOLE SYSTEM APPROACH

The main types of responses to climate change identified in the previous section illuminate the cross-scale processes, providing an insight into the adaptation dynamics (Fig. 2). The interplay between adaptation strategies at different levels contributes to the resilience of the whole system through (i) the links between natural and cultivated landscapes; (ii) the supportive role of agriculture in the protection and restoration of ecosystems; and (iii) the maintenance of species and genetic diversity.

Figure 2 – Adaptation dynamics.

THE LINKS BETWEEN NATURAL AND CULTIVATED LANDSCAPES

In many traditional agricultural landscapes, the wild and cultivated areas are integrated under a management system to complement each other. For instance, the common practice of rotational farming (shifting cultivation) exemplifies a situation in which it is often difficult to distinguish between cultivated and wild or natural landscapes. Within cultivated fields, where crops are planted, wild species are also recruited and tended. Various forms of forests and individual trees, though not planted, are cared for, managed and used for food, fuel, medicine, timber and various other necessities (Rerkasem et al., 2009).

The wild areas provide services essential for the resilience of the cultivated regions including erosion control, microclimate regulation, pest regulation and pollination. Wild species provide alternative sources of food and income during the periods of bad harvest or herd loss due to unfavourable weather conditions. Many communities harvest wild vegetables, fruits, tubers and other edibles from the forest during the year, especially during the season of greatest food scarcity.

Wild species with traits such as tolerance of extreme temperatures and salinity are becoming increasingly important resources for communities. In Bangladesh flood-affected communities cultivate saline-tolerant varieties of reeds and saline-tolerant and drought-resistant fruit and timber trees, to reduce vulnerability to floods and sea-level rise and ensure longer-term income generation. This involved the establishment of community tree nurseries and distribution of indigenous varieties of coconut, mango and other fruit species as well as mangrove-associated species (Selvaraju et. al., 2006).

THE ROLE OF AGRICULTURE IN ECOSYSTEM PROTECTION AND RESTORATION

Sustainable types of agriculture can reduce the adverse impacts of climate change on fragile ecosystems and encourage rehabilitation of degraded landscapes, as illustrated by the following examples. In Rajasthan, India, where drought and environmental degradation severely impaired the livelihood security of local communities; a community-led, watershed-restoration programme reinstated johads, a traditional rainwater-harvesting system. Johads are simple concave mud barriers, built across small, uphill river tributaries to collect water and encourage groundwater recharge and improve forest growth, while providing water for irrigation, domestic use, livestock and wildlife (McNeely and Scherr, 2001). Restoration of over 5000 johads in 1000 villages has resulted in the restoration of the Avari River and the return of native bird populations (Narain et al., 2005). In Honduras and Nicaragua, an increasing number of farmers are abandoning the slash-and-burn technique and adopting the Quezungal slash-and-mulch agroforestry system, which draws on traditional practices of tree management and reduces crop damage caused by natural disasters (Bergkamp et al., 2003). In Honduras, the result has been the natural regeneration of around 60 000 ha of secondary forest, restoration of soil quality, and consequently better crop yields (New Agriculturalist, 2009b).

THE MAINTENANCE OF SPECIES AND GENETIC DIVERSITY

Cultivation of a high level of diversity in an agricultural system strengthens the system’s resilience. In turn, agricultural systems with diverse species and varieties of crops and livestock provide for the maintenance (in situ conservation) of diversity and the evolution of continually adapted populations. In many cases, introgression of genes from wild relatives or cross pollination results in new genotypes or helps to maintain the broad genetic base within crops In situ conservation of the agricultural diversity of genes and species often occurs within a mosaic of agricultural landscapes consisting of home gardens, fields, groves and orchards, and boundaries and niches that create diverse selection and adaptation factors through exposure to the environmental change. An example of the importance of genetic diversity has been the maintenance of traditional pearl millet and sorghum varieties in Niger and Mali over the past 20-30 years. While varietal identity has often altered over this period, total diversity and average yields have remained broadly unchanged, despite periods of significant drought and the occurrence of other environmental and social stresses. It appears these materials show sufficient adaptability to enable farmers to cope, at least partially, with periods of significant rainfall shortage and that farming practices and local institutions have favoured the maintenance of diversity (Kouressy et al., 2003; Bezançon et al., 2009). Interestingly, in both countries, there was some loss of long-duration types with an apparent increasing preference for rapidly maturing varieties.

COMMUNITY DIMENSION OF ADAPTATION

Adaptive management of agrobiodiversity involves activities at both the individual and community levels. At the individual farmer level, agricultural systems are diversified and various management practices adjusted. However, the adaptive management of water, soil and agrobiodiversity takes place at the ecosystem or landscape level and requires communal efforts, often regulated through social institutions. Local institutions that endorse the sustainable management of agrobiodiversity and landscapes have been re-established in several adaptation projects. In Niger, the Tuareg nomads have protected and improved their pastureland through pasture-management associations; thereby strengthening the resilience to both climatic and non-climatic pressures (New Agriculturist, 2009a). In a mountainous region of Ecuador, a community-based initiative has promoted sustainable use of resources to prevent ecosystem degradation resulting from inappropriate agricultural practices and overgrazing (Equator Initiative, 2004). The Turkana pastoralists in northern Kenya, and Sukuma agro pastoralists in Shinyanga, Tanzania, have restored degraded woodlands through the revival of local institutions for natural resource management (Barrow and Mlenge, 2003). The Turkana restored over 30 000 ha and the Sukuma 250 000 ha of woodland; which has resulted in a mitigation of risks associated with droughts (ibid).

The need to replenish diversity in agricultural systems has encouraged the community management of genetic resources. This has resulted in the establishment of community seed banks to facilitate the revival and distribution of traditional and stress-tolerant crops and varieties. In Uttar Pradesh, India, the establishment of seed banks to facilitate the diversification of local food systems is one of the flood coping mechanisms (Wajih, 2008).

Just as local crops and varieties needed to be reintroduced or new crops introduced, in some cases, traditional practices have also had to be adjusted. Indigenous forecasting techniques have become less reliable due to the increasing variability and irregularity of rainfall. Many Javanese farmers base their planting schedule on the Javanese lunar cyclical calendar, as well as observations of the environment, yet both are becoming unreliable. Instead of relying on observations that used to indicate the start of the rainy season such as falling leaves, singing birds or noisy insects, the farmer began using climate forecasts and other agro-meteorological information (Winarto et al., 2008). In other places farmers have begun documenting climate change impacts at local level (Ulsrud et al., 2008).

WOMEN’S ROLE IN ADAPTATION

Many projects concerned with the protection of agrobiodiversity are initiated and managed by local women’s groups. In India, women have initiated and engaged in a number of adaptation projects, which involve the revival of traditional seeds and the establishment of community seed banks. In Sri Lanka, a women-led project has been promoting the cultivation of indigenous roots and tuber crops, organic agriculture and integrated pest management, and seed bank establishment (Equator Initiative, 2008c). Women’s groups are also involved in ecosystem protection and restoration projects. An example comes from Senegal, where a collective of women’s groups in nine villages manages mangrove nurseries and reforestation. The group has made significant contributions towards restoring the mangroves and protection of biodiversity, which has encouraged the return of wildlife (Equator Initiative, 2008d).

INTEGRATING ADAPTATION AND LIVELIHOODS WITH THE PROTECTION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTS

Adaptation projects are closely linked to the initiatives aiming to protect traditional knowledge and indigenous people’s rights. Many adaptation projects are initiated, supported and carried out by indigenous communities trying to protect their rights to ancestral lands and culture. In the Philippines, an organization of the Kalinga indigenous peoples, working on, among other issues, the protection of biodiversity and indigenous rights, is engaged in a number of activities of critical importance to the resilience of local food systems such as watershed rehabilitation, reforestation, and rice terrace rehabilitation. The organization aims to achieve sustainable livelihoods through the indigenous forest, watershed, irrigation and ecoagriculture management systems; and protect the rights of Kalinga indigenous peoples and their ownership over ancestral lands (Equator Initiative, 2004a).

In Colombia, Panama, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Thailand, India and other countries, indigenous organisations are actively involved in the protection of traditional knowledge and reintroduction of indigenous crop varieties of vegetables, tubers, grains, beans and fruit. The Potato Park in Cusco, Peru was created in 2005 to protect the genetic diversity of local potato varieties and associated indigenous knowledge. The project demonstrates the link between the protection of agrobiodiversity and the protection of indigenous people’s rights, livelihoods and culture. Indigenous Quechua communities involved in the project have brought back from a gene bank into their fields over 400 potato varieties to ensure the adaptation to changing climatic conditions (Argumedo, 2008). The park has organised indigenous technical experts to monitor changes and identify responses and innovations that are consistent with the cultural imperatives and livelihood needs of Andean communities (ibid).

CONCLUSIONS

Three general conclusions can be drawn from this analysis of the different ways in which indigenous and traditional agricultural communities are coping with climate change. Firstly, adapting to climate change has usually involved a range of different actions at all three levels; ecosystem or landscape, farm or agricultural system, and involving both inter- and intra-specific diversity. Secondly, innovation based on both traditional knowledge and new information has been important, and social (e.g. community) cultural and political dimensions have played a key role. Thirdly, use of traditional crop and livestock species and varieties, with new materials where necessary, has been a common feature. From these follow a number of specific conclusions that can provide a basis for action to support adaptation by indigenous and traditional agricultural communities.

- The resilience of local food systems and their adaptation to change can be enhanced through a strategy of diversification within landscape and agricultural system or farm. This may be achieved using a range of different approaches including agroforestry, maintenance of a diversity of crop species and varieties, and increased use of agro-ecosystem-associated biodiversity and is equally appropriate in dryland, mountain, humid tropic and coastal environments.

- Ecosystem protection and restoration, landscape rehabilitation and reforestation can reduce the adverse effects of climate change on local food systems. They reduce the vulnerability to extreme weather events, drought, excessive rainfall and seawater intrusion, and help ensure ecosystem services such as pollination, pest regulation and erosion control.

- Resilience and adaptability seem to be enhanced by the use of sustainable agricultural practices (e.g. low-input agriculture). High-input agricultural practices and the ecosystem degradation often associated with their use accelerate the loss of agrobiodiversity, soil erosion and water depletion, and thereby aggravate the vulnerability of traditional agricultural communities to climate change.

- Adaptation involves the continuing maintenance in production systems of intra- and inter-species diversity using traditional crop and livestock species and varieties and access to new diversity. Maintenance of sufficient diversity allows farmers to improve stress tolerance through selection and breeding techniques, and enables the natural process of adaptation to operate under the changing agro-ecological conditions. Access to new crop and livestock materials can also be an important part of coping strategies.

- Adaptation solutions are local. Protection and restoration of ecosystems, diversification of agricultural landscapes and the protection and use of agrobiodiversity de.ne an adaptation framework that can be applied in different environments. However, the choice and design of specific strategies are based on local experiences of climate change, needs, resources, knowledge and agricultural traditions.

- Adaptation activities are undertaken at the community level. Many of the challenges cannot be met at the level of the individual or farm and require community involvement. Community institutions play an important part in adaptation. Women as custodians of agrobiodiversity often play a key role in adaptation activities.

- The need to adapt to climate change has often led to the revival of traditional practices and agricultural systems. Traditional agricultural practices and land-management techniques, especially in stress-prone environments, can help ensure productivity under adverse conditions through the management of microclimate and soil and water resources.

- The continuous process of innovation required to cope with climate change involves the use of traditional knowledge combined with access to new knowledge. Local management systems of ecosystems, landscapes, agricultural systems and genetic material are often harmonised with and adjusted to changing agro-climatic conditions. At the same time new knowledge is also needed to cope with changing circumstances and the introduction of new materials.

- Local agrobiodiversity-based solutions create opportunities for integration of adaptation and protection of indigenous peoples’ rights. Many adaptation initiatives mentioned in this paper are initiated, supported or managed by indigenous communities. Their adaptive capacity often depends on their ability to access their ancestral lands and protect their cultural heritage.

There remain a number of areas where we urgently need further work. one particular area is the social, cultural and political dimensions of adaptation. In a number of cases it is clear that an innovation based on traditional knowledge can lead to development of local adaptation measures that protect ecosystems and agrobiodiversity, and empower indigenous and traditional agricultural communities. This link between empowerment of communities and adaptation needs to be better understood. There is also a need to develop indicators of adaptation, adaptability and resilience that are useful at different levels and some communities and groups have already embarked on this. These indicators will help to identify what contribution agrobiodiversity can make and where it is likely to be most useful.

From the conclusions listed above it is possible to identify the kinds of activities that are likely to support the use of agrobiodiversity by traditional rural communities and indigenous peoples as part of their coping strategies. The support for, and maintenance of, local social and cultural institutions can obviously play an important part. Empowering communities so as to enable them to carry out interventions at ecosystem or landscape level can also be important. The need to ensure continuing access to a range of diverse crop varieties, agroforestry species and livestock types and their maintenance, is essential. This may best be combined with the further development of such materials through locally based selection or breeding activities. Way of supporting the maintenance of traditional knowledge combined with access to new information will be important as part of adaptation, as will the development and adoption of locally appropriate improved agronomic practices.

The results and conclusions show that agrobiodiversity has a key role to play in adaptation to climate change and to improving adaptability and resilience in agro ecosystems. It is essential that international and national policy debates on adaptation to climate change begin to take account of the rich experience and the actions already undertaken by traditional communities and indigenous peoples and to ensure their full involvement in debates on policies and actions required.

REFERENCES

Adger WN, Agrawala S, Mirza MMQ, Conde C, O’Brien K, Pulhin J, Pulwarty R, Smit B, Takahashi K. 2007. Assessment of adaptation practices, options, constraints and capacity. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 717-743.

Adger WN. 2006. Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 16(3):268–281.

Argumedo A. 2008. Association ANDES: Conserving indigenous biocultural heritage in Peru. IIED Gatekeeper Series/International Institute for Environment and Development, Sustainable Agriculture Programme No. 137a. IIED. Natural Resources Group and Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Programme, London, UK.

Barrow E, Mlenge W. 2003. Trees as key to pastoralist risk management in semi-arid landscapes in Shinyanga, Tanzania and Turkana, Kenya. Presented at the CIFOR-FLR Conference, Bonn, Germany, May 2003.

Bergkamp G, Orlando B, Burton I. 2003. Change: adaptation of water resources management to climate change. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland.

Bezançon G, Pham JL, Deu M, Vigouroux Y, Sagnard F, Mariac C, Kapran I, Mamadou A, Gérard B, Ndjeunga J, Chantereau J. 2009. Changes in the diversity and geographic distribution of cultivated millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) varieties in Niger between 1976 and 2003. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 56:223–236.

Bonifacio E, Zanini E. 1999. Sustainable domestication of indigenous fruit trees: the interaction between soil and biotic resources in some drylands of southern Africa. UNESCO Best Practices on Indigenous Knowledge.

Equator Initiative. 2004. Asociación de Trabajadores Autónomos San Rafael – Tres Cruces – Yurac Rumi (ASARATY) – Ecuador. http://equatorinitiative.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=491& Itemid=531&idx=49. Accessed 11 March 2010.

Equator Initiative. 2004a. Kalinga Mission for Indigenous Children and Youth Development, Inc. – Philippines. http://www.equatorinitiative.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=482:kamicydi&catid=1 05:equator-prize-winners-2004&Itemid=541&lang=es. Accessed 11 March 2010.

Equator Initiative. 2008b. Camalandaan Agroforest Farmers Association – Philippines. http://equatorinitiative. org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=530&Itemid=531&idx=86. Accessed 10 March 2010.

Equator Initiative 2008c. Community Development Centre – Sri Lanka. http://equatorinitiative.org/index. php?option=com_content&view=article&id=527&Itemid=531&idx=87. Accessed 11 March 2010.

Equator Initiative 2008d. Fédération Régionale des Groupements de Promotion Féminine Ziguinchor. http:// equatorinitiative.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=520&Itemid=531&idx=81. Accessed 25 February 2010.

FAO. 2010a. Homestead gardens in Bangladesh. Technology for agriculture. Proven technologies for small holders. http://www.fao.org/teca/content/homestead-gardens-bangladesh. Accessed 24 April 2010.

FAO. 2010b. Incorporation of tree management into land management in Jamaica – guinea grass mulching. Technology for agriculture. Proven technologies for small holders. http://www.fao.org/teca/content/ incorporation-tree-management-land-management-jamaica-%C2%BF-guinea-grass-mulching. Accessed 24 March 2010.

Haq R, Kumar T, Ghosh P. 2009. Soil-less agriculture gains ground. LEISA Magazine 25(1):35.

Ho R. 2002. Waru waru, a cultivation and irrigation system used in flood-prone areas of the Altiplano. In: Boven K, Morohashi J, editors. Best practices using indigenous knowledge. Nuffic, the Hague, the Netherlands and UNESCO/MOST, Paris, France.

IISD. 2003a. Increasing the resilience of tropical hillside communities through forest landscape restoration. Climate change, vulnerable communities and adaptation. IISD Information Paper 2.

IISD. 2003b. Sustainable drylands management: a strategy for securing water resources and adapting to climate change. Climate change, vulnerable communities and adaptation. IISD Information Paper 3.

Kieft J. 2001. Indigenous variety development in food crops strategies on Timor: their relevance for in situ biodiversity conservation and food security. Indigenous Knowledge and Development Monitor 9-2.

Kouressy M, Bazile D, Vaksmann M, Soumare M, Doucoure T, Sidibe A. 2003. La dynamique des agroécosystèmes : un facteur explicatif de l’érosion variétale du sorgho Le cas de la zone Mali-Sud. In: Dugué P, Jouve Ph, éds. Organisation spatiale et gestion des ressources et des territoires ruraux. Actes du colloque international, 25-27, Montpellier, France. Umr Sagert, Cnearc.

Mapfumo P, Chikowo R, Mtambanengwe F, Adjei-Nsiah S, Baijukya F, Maria R, Mvula A, Giller K. 2008. Farmers’ perceptions lead to experimentation and learning, LEISA Magazine 24(4):30-31

McNeely JA, Scherr SJ. 2001. Common Ground, Common Future. How ecoagriculture can help feed the world and save wild biodiversity. IUCN – the World Conservation Union, Future Harvest.

Mitin A, 2009. Documentation of selected adaptation strategies to climate change in rice cultivation. East Asia Rice Working Group. http://www.eastasiarice.org/Books/Adaptation%20Strategies.pdf. Accessed 22 March 2010.

Morton JF. 2007. The impact of climate change on smallholder and subsistence agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA 104:19680-19685.

Narain P, Khan MA, Singh G. 2005. Potential for water conservation and harvesting against drought in Rajasthan, India. Working paper 104, Drought series: paper 7. International Water Management Institute, Sri Lanka.

Navdanya. 2009. www.navdanya.org. Accessed 26 March 2010.

New Agriculturalist. 2009a. Pastoralists: moving with the times? http://www.new-ag.info/focus/focusItem. php?a=966. Accessed 18 March 2010.

New Agriculturalist. 2009b. Ancient lesson in agroforestry – slash but don’t burn. http://www.new-ag.info/ focus/focusItem.php?a=1030. Accessed 18 March 2010.

Ouédrago E, Mando A, Brussard L. 2008. Termites and mulch work together to rehabilitate soils. LEISA Magazine 24(2):28.

Pratap U. 2008. Successful pollination of apples. Bees for Development Journal. http://www. beesfordevelopment.org/info/info/pollination/successful-pollination-of.shtml. Accessed 30 March 2010.

Reij C, Nasr N, Chahbani, B. 2002. Innovators in land husbandry in arid areas of Tunisia. In: Boven K, Morohashi, J, editors. Best practices using indigenous knowledge. Nuf.c, the Hague, the Netherlands, UNESCO/MOST, Paris, France.

Rerkasem K, Yimyam N, Rerkasem B. 2009. Land use transformation in the mountainous mainland Southeast Asia region and the role of indigenous knowledge and skills in forest management. Forest Ecology and Management. 257:2035–2043.

Salick J, Byg A. 2007. Indigenous peoples and climate change. University of Oxford, Oxford and the Missouri Botanical Garden, Missouri.

Selvaraju R, Subbiah AR, Baas S, Juergens I. 2006. Livelihood adaptation to climate variability and change in drought-prone areas in Bangladesh – case study. FAO, Rome, Italy.

Shah R, Ameta N. 2008 Adapting to change with a blend of traditional and improved practices. LEISA Magazine 24(4)9-11.

Taonda J-B, Hien F, Zango C. 2001. Namwaya Sawadogo: The ecologist of Touroum, Burkina Faso. In: Reij C, Waters-Bayer A, editors. Farmer innovation in Africa: a source of inspiration for agricultural development. Earthscan, London, UK.

Ulsrud K, Sygna L, O’Brien K. 2008. More than rain: identifying sustainable pathways for climate adaptation and poverty reduction. The Development Fund/Utviklingsfondet. http://www.utviklingsfondet.no/English/For_ partners/Lessons_learnt/More_than_Rain. Accessed 7 March 2010.

UNFCCC. 2010. The UNFCCC local coping strategies database. http://maindb.unfccc.int/public/adaptation/. Accessed 5 March 2010.

USC Canada. 2008. Growing resilience: seeds, knowledge and diversity in Honduras. Canadian Food Security Policy Group. http://www.ccic.ca/_.les/en/working_groups/003_food_2009-03_case_study_honduras.pdf. Accessed 7 March 2010.

Vakeesan A, Nishanthan T, Mikunthan G. 2008. Green manures: nature’s gift to improve soil fertility, LEISA Magazine 24(2)16-17.

Vershot LV, Mackensen J, Kandji S, Noordwijk M, Tomich T, ong C, Albrecht A, Bantilan C, Anupama KV, Palm C. 2005. Opportunities for linking adaptation and mitigation in agroforestry systems. http://www. worldagroforestry.org/downloads/publications/PDFS/BC04241.pdf. Accessed 1 March 2010.

Walker B, Holling CS, Carpenter SR, Kinzig A. 2004. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society 9(2):art. 5.

Wajih SA. 2008. Adaptive agriculture in flood affected areas. LEISA Magazine 24(4):24-25

Winarto YT, Stigter K, Anantasari E, Hidayah SN. 2008. Climate field schools in Indonesia: improving “response farming“ to climate change. LEISA Magazine 24(4)24-25.

Wetlands International. 2009. www.wetlands.org. Accessed 8 March 2010.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: This paper synthesizes the results of work undertaken by the Platform for Agrobiodiversity Research as part of its project on “The use of agrobiodiversity by indigenous peoples and rural communities in adapting to climate change”. An earlier version of the paper was discussed during a workshop held in Chiang Mai, Thailand in June 2009. The financial, scientific and technical support of the Christensen Fund, Bioversity International and the Chiang Mai University are gratefully acknowledged. The paper was prepared by Dunja Mijatovic with assistance from Paul Bordoni, Pablo Eyzaguirre, Elizabeth Fox, Sara Hutchinson, Frederick van Oudenhoven and Toby Hodgkin.

Photographs: cover, page 27 ©FAO/Peter DiCampo; page 5 ©Tim Murray; page 8, 26 ©FAO/Pietro Cenini; page 3, 10, 17, 21 ©Paola De Santis; page 13 ©FAO/E.Yeves; page 14, 19 ©FAO/Giulio Napolitano; page 24 ©PAR/Paul Bordoni.

State to import fertiliser ahead of planting season

State to import fertiliser ahead of planting season Drought situation

Drought situation