Growing demand for food and fuel has put pressure on the world’s agricultural lands to produce more. Now, a trend in “land grabbing” has emerged, as wealthy countries lease or buy farms and agribusiness in poorer countries to ensure their own future supplies. The result may be further economic disparities and even “food wars.”

World grain and soybean prices more than doubled between 2007 and mid-2008. As food prices climbed everywhere, some exporting countries began to restrict grain shipments in an effort to limit food price inflation at home. Importing countries panicked. Some tried to negotiate long-term grain supply agreements with exporting countries, but in a seller’s market, few were successful. Seemingly overnight, importing countries realized that one of their few options was to find land in other countries on which to produce food for themselves.

And the land rush was on.

Looking for land abroad is not entirely new. Empires expanded through territorial acquisitions, colonial powers set up plantations, and agribusiness firms try to expand their reach. Agricultural analyst Derek Byerlee tracks market-driven investments in foreign land back to the mid-nineteenth century. During the last 150 years, large-scale agricultural investments from industrial countries concentrated primarily on tropical products such as sugarcane, tea, rubber, and bananas.

What is new now is the scramble to secure land abroad for more basic food and feed crops—including wheat, rice, corn, and soybeans—and for biofuels. These land acquisitions of the last several years, or “land grabs” as they are sometimes called, represent a new stage in the emerging geopolitics of food scarcity. They are occurring on a scale and at a pace not seen before.

The “Grabbers”: Searching for Stable Food Supplies

Saudi Arabia, South Korea, China, and India are among the countries that are leading the charge to buy or lease land abroad, either through government entities or through domestically based agribusiness firms. Saudi Arabia’s population has simply outrun its land and water resources. The country is fast losing its irrigation water and will soon be totally dependent on imports from the world market or overseas farming projects for its grain.

South Korea imports more than 70% of its grain, and it has become a major land investor in several countries. In an attempt to acquire 940,000 acres of farmland abroad by 2018 for corn, wheat, and soybean production, the Korean government will reportedly help domestic companies lease farmland or buy stakes in agribusiness firms in countries such as Cambodia, Indonesia, and Ukraine.

China is also nervous about its future food supply, as it faces aquifer depletion and the heavy loss of cropland to urbanization and industrial development. Although it was essentially self-sufficient in grain from 1995 onward, within the last few years China has become a leading grain importer. It is by far the top importer of soybeans, bringing in more than all other countries combined.

India has also become a major player in land acquisitions, with its huge and growing population to feed. Irrigation wells are starting to go dry, so with the projected addition of 450 million people by mid-century and the prospect of growing climate instability, India, too, is worried about future food security.

Among the other countries jumping in to secure land abroad are Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). For example, in early 2012 Al Ghurair Foods, a company based in the UAE, announced it would lease 250,000 acres in Sudan for 99 years on which to grow wheat, other grains, and soybeans. The plan is that the resulting harvests will go to the UAE and other Gulf countries.

Tracking the Trends

Accurate information has been difficult to find for those tracking this worldwide land-grab surge. Perhaps because of the politically sensitive nature of land grabs, separating rumor from reality remains a challenge.

At the outset, the increasing frequency of news reports mentioning deals seemed to indicate that the phenomenon was growing, but no one was systematically aggregating and verifying data on this major agricultural development. Many groups have relied on GRAIN (www.grain.org), a small nongovernmental organization with a shoestring budget, and its compilations of media reports on land grabs. A much-anticipated World Bank report, first released in September 2010 and updated in January 2011, used GRAIN’s online collection to aggregate land-grab information, noting that GRAIN’s was the only tracking effort that was global in scope.

In its report, the World Bank identified 464 land acquisitions that were in various stages of development between October 2008 and August 2009. It reported that production had begun on only one-fifth of the announced projects, partly because many deals were made by land speculators. The report offered several other reasons for the slow start, including “unrealistic objectives, price changes, and inadequate infrastructure, technology, and institutions.”

The amount of land involved was known for only 203 of the 464 projects, yet it still came to some 140 million acres—more than is planted in corn and wheat combined in the United States. Particularly noteworthy is that, of the 405 projects for which commodity information was available, 21% were slated to produce biofuels and another 21% were for industrial or cash crops, such as rubber and timber. only 37% of the projects involved food crops.

Nearly half of these land deals, and some two-thirds of the land area, were in sub-Saharan Africa—partly because land is so cheap there compared with land in Asia. In a careful evidence-based analysis of land grabs in sub-Saharan Africa between 2005 and 2011, George Schoneveld from the Center for International Forestry Research reported that two-thirds of the area acquired there was in just seven countries: Ethiopia, Ghana, Liberia, Madagascar, Mozambique, South Sudan, and Zambia. In Ethiopia, for example, an acre of land can be leased for less than $1 a year, whereas in land-scarce Asia it can easily cost $100 or more.

The second most-targeted region for land grabs was Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Laos, the Philippines, and Indonesia. Countries have also sought land in Latin America, especially in Brazil and Argentina. The state-owned Chinese firm Chongqing Grain Group, for example, has reportedly begun harvesting soybeans on some 500,000 acres in Brazil’s Bahia state for export to China. The company announced in early 2011 that, as part of a multibillion-dollar investment package in Bahia, it would develop a soybean industrial park with facilities capable of crushing 1.5 million tons of soybeans a year.

Unfortunately, the countries selling or leasing their land for the production of agricultural commodities to be shipped abroad are typically poor and, more often than not, those where hunger is chronic, such as Ethiopia and South Sudan. Both of these countries are leading recipients of food from the UN World Food Programme. Some of these land acquisitions are outright purchases of land, but the overwhelming majority are long-term leases, typically 25 to 99 years.

Food and Fuel Compete for Agricultural Land

In response to rising oil prices and a growing sense of oil insecurity, energy policies encouraging the production and use of biofuels are also driving land acquisitions. This results in either clearing new cropland or making existing cropland unavailable for food production.

The European Union’s renewable energy law requires 10% of transport energy to come from renewable sources by 2020. This law is encouraging agribusiness firms to invest in land to produce biofuels for the European market. In sub-Saharan Africa, many investors have planted jatropha (an oilseed-bearing shrub) and oil palm trees, both sources for biodiesel.

One company, U.K.-based GEM BioFuels, has leased 1.1 million acres in 18 communities in Madagascar on which to grow jatropha. At the end of 2010 it had planted 140,000 acres with this shrub. But by April 2012 it was reevaluating its Madagascar operations due to poor project performance. Numerous other firms planning to produce biodiesel from jatropha have not fared much better. The initial enthusiasm for jatropha is fading as yields are lower than projected and the economics just do not work out.

Sime Darby, a Malaysia-based company that is a big player in the world palm oil economy, has leased 540,000 acres in Liberia to develop oil palm and rubber plantations. It planted its first oil palm seedling on the acquired land in May 2011, and the company plans to have it all in production by 2030.

Thus, we are witnessing an unprecedented scramble for land that crosses national boundaries. Driven by both food and energy insecurity, land acquisitions are now also seen as a lucrative investment opportunity. Fatou Mbaye of Action Aid in Senegal observes, “Land is quickly becoming the new gold and right now the rush is on.”

Investing—or Speculating—in Land

Investment capital is coming from many sources, including investment banks, pension funds, university endowments, and wealthy individuals. Many large investment funds are incorporating farmland into their portfolios. In addition, there are now many funds dedicated exclusively to farm investments. These farmland funds generated a rate of return from 1991 to 2010 that was roughly double that from investing in gold or the S&P 500 stock index and seven times that from investing in housing. Most of the rise in farmland earnings has come since 2003.

Many investors are planning to use the land acquired, but there is also a large group of investors speculating in land who have neither the intention nor the capacity to produce crops. They sense that the recent rises in food prices will likely continue, making land even more valuable over the longer term. Indeed, land prices are on the rise almost everywhere.

Land acquisitions are also water acquisitions. Whether the land is irrigated or rainfed, a claim on the land represents a claim on the water resources in the host country. This means land acquisition agreements are a particularly sensitive issue in water-stressed countries.

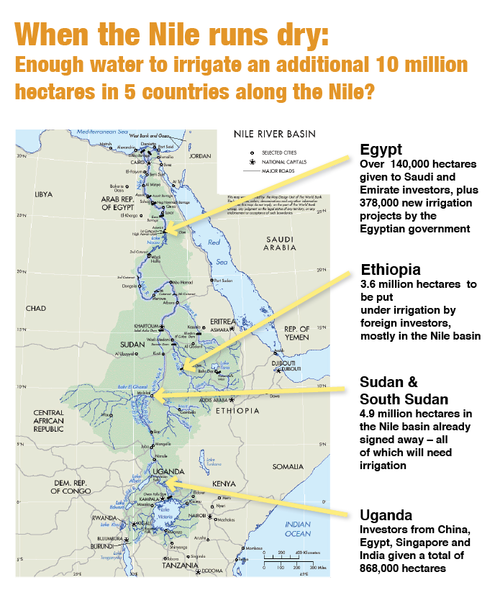

In an article in Water Alternatives, Deborah Bossio and colleagues analyze the effect of land acquisition in Ethiopia on the demand for irrigation water and, in turn, its effect on the flow of the Nile River. Compiling data on 12 confirmed projects with a combined area of 343,000 acres, they calculate that if this land is all irrigated, as seems likely, the irrigated area in the region would increase sevenfold. This would reduce the average annual flow of the Blue Nile by approximately 4%.

Acquisitions in Ethiopia, where most of the Nile’s headwaters begin, or in the Sudans, which also tap water from the Nile, mean that Egypt will get less water, thus shrinking its wheat harvest and pushing its already heavy dependence on imported wheat even higher.

Land Grabs and Human Rights

Massive land acquisitions raise many questions. Since productive land is not often idle in the countries where the land is being acquired, the agreements mean that many local farmers and herders will simply be displaced. Their land may be confiscated, or it may be bought from them at a price over which they have little say, leading to the public hostility that often arises in host countries.

In addition, the agreements are almost always negotiated in secret. Typically only a few high-ranking officials are involved, and the terms are often kept confidential. Not only are key stakeholders such as local farmers not at the negotiating table, they often do not even learn about the agreements until after the papers are signed and they are being evicted. Unfortunately, it is often the case in developing countries that the state, not the farmer, has formal ownership of the land. Against this backdrop, the poor can easily be forced off the land by the government.

The displaced villagers will be left without land or livelihoods in a situation where agriculture has become highly mechanized and employs few people. The principal social effect of these massive land acquisitions may well be an increase in the ranks of the world’s hungry.

The Oakland Institute, a California-based think tank, reports that Ethiopia’s huge land leases to foreign firms have led to “human rights violations and the forced relocation of over a million Ethiopians.” Unfortunately, since the Ethiopian government is pressing ahead with its land lease program, many more villagers are likely to be forcibly displaced.

In a landmark article on African land grabs in the Observer, John Vidal quotes Nyikaw Ochalla, an Ethiopian from the Gambella region: “The foreign companies are arriving in large numbers, depriving people of land they have used for centuries. There is no consultation with the indigenous population. The deals are done secretly. The only thing the local people see is people coming with lots of tractors to invade their lands.” Referring to his own village, where an Indian corporation is taking over, Ochalla says, “Their land has been compulsorily taken and they have been given no compensation. People cannot believe what is happening.”

Hostility of local people to land grabs is the rule, not the exception. China, for example, signed an agreement with the Philippine government in 2007 to lease 2.5 million acres of land on which to produce crops that would be shipped home. once word leaked out, the public outcry—much of it from Filipino farmers—forced the government to suspend the agreement. A similar situation developed in Madagascar, where a South Korean firm, Daewoo Logistics, had pursued rights to more than 3 million acres of land, an area half the size of Belgium. This helped stoke a political furor that led to a change in government and cancellation of the agreement.

Impacts of “Long-Distance Farming”

How productive will the land be that actually ends up being farmed? Given the level of agricultural skills and technologies likely to be used, in most cases robust gains in yields could be expected. As demonstrated in Malawi, simply applying fertilizer to nutrient-depleted soils where rainfall is adequate and using improved seed can easily double grain yields.

Perhaps the more important question is, What will be the effects on the local people? The Malawi program’s approach of directly helping local farmers can dramatically expand food production, raise the income of villagers, reduce hunger, and earn foreign exchange—a win-win-win-win situation. This contrasts sharply with the lose-lose-lose situation accompanying land grabs—villagers lose their land, their food supply, and their livelihoods.

There will be some spectacular production gains in some countries; there will undoubtedly also be failures. Some projects have already been abandoned. Many more will be abandoned simply because the economics do not pan out. Long-distance farming, with the transportation and travel involved, can be costly, particularly when oil prices are high.

Overall, while announcements of new land acquisitions have been popping up with alarming frequency, the actual development of acquired land has been slow. Investors tend to focus on the costs of producing the crops without sufficiently considering the cost of building the modern agricultural infrastructure needed to support successful development of the tracts of acquired land. In most sub-Saharan African countries, there is little of this infrastructure, which means the cost to an investor of developing it can be overwhelming.

In some countries, it will take years to build the roads needed to both bring in agricultural inputs, such as fertilizer, and move the farm products out. Beyond this, there is a need for a local supply of either electric power or diesel fuel to operate irrigation pumps. A full-fledged farm equipment maintenance support system is needed, lest equipment is left idle while waiting for repair people and parts to come from afar. Maintaining a fleet of tractors, for example, requires not only trained mechanics but also an on-site inventory of things like tires and batteries. Grain elevators and grain dryers are essential for storing grain. Fertilizer and fuel storage facilities have to be constructed.

Another complicating factor is navigating the various governmental regulations and procedures. For example, as almost all the equipment and inputs needed in a modern farming operation have to be imported, this requires a familiarity with customs procedures. In addition, various permits may be required for such things as drilling irrigation wells, building irrigation canals, or tapping into the local electrical grid if one exists.

When Saudi Arabia decided to invest in cropland, it created King Abdullah’s Initiative for Saudi Agricultural Investment Abroad, a program to facilitate land acquisitions and farming in other countries, including Sudan, Egypt, Ethiopia, Turkey, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Brazil. The Saudi Ministry of Commerce and Industry recently launched an inquiry to find out why things were moving at such a glacial pace. What it learned was that simply acquiring tracts of land abroad is only the first step. Modern agriculture depends on heavy investment in a supporting infrastructure, something that is costly even for the oil-rich Saudis.

There is also a huge knowledge deficit associated with launching new farming projects in countries where soils, climate, rainfall, insect pests, and crop diseases are far different from those in the investor country. There almost certainly will be unforeseen outbreaks of plant disease and insect infestations as new crops are introduced, particularly since so many of the land deals are in tropical and subtropical regions.

A lack of familiarity with the local environment brings with it a wide range of risks. The Indian firm Karuturi Global is the world’s largest producer of cut roses, which it grows in Ethiopia, Kenya, and India for high-income markets. The company has recently entered the land rush, jumping at an offer in 2008 to farm up to 740,000 acres of land in Ethiopia’s Gambella region. In 2011, the company planted its first corn crop in fertile land along the Baro River. Recognizing the possibility of flooding, Karuturi invested heavily in building dikes along the river. Unfortunately the dikes were not sufficient, and 50,000 tons of corn were lost to flash flooding. Fortunately for Karuturi, the company was large enough to survive this heavy loss.

The bottom line is that investors face steep cost curves in bringing this land into production. Even though the land itself may be relatively inexpensive, the food grown under these conditions and shipped to home countries will be some of the most costly food ever produced.

The flurry of large-scale land acquisitions that began in 2008, yielded only a few relatively small harvests as of 2012. The Saudis harvested their first rice crop in Ethiopia, albeit a very small one, in late 2008.

In 2009, South Korea’s Hyundai Heavy Industries harvested some 4,500 tons of soybeans and 2,000 tons of corn on a 25,000-acre farm it took over from Russian owners, roughly 100 miles north of Vladivostok. Hyundai had planned to expand production rapidly to 100,000 tons of corn and soybeans by 2015. But in 2012 it anticipated producing only 9,000 tons of crops, putting it far behind schedule for reaching its 2015 goal. The advantage for Hyundai was that this was already a functioning farm. The supporting infrastructure was already in place. Yet even if Hyundai reaches its 100,000-ton goal, this will cover just 1% of South Korea’s consumption of these commodities.

Another of the acquisitions that appears to be progressing is in South Sudan, where Citadel Capital, an Egyptian private equity company, has leased 260,000 acres for agriculture. In 2011 it began production with a 1,500-acre trial of chickpeas. The plan is to scale the area in chickpeas up to 130,000 acres in five years. The overall goal is to grow crops, eventually including corn and sorghum as well, for which there is a large local market and to produce them at well under the price of imports. This particular project is apparently intended to produce for local consumption. Unfortunately, this is not the case for the great majority of foreign acquisitions.

Resources on Food and Agricultural Land Use

Online:

- GRAIN, www.grain.org

- International Food Policy Research Institute, www.ifpri.org

- International Institute for Environment and Development,www.iied.org

- Land Matrix,http://landportal.info/landmatrix

Print:

- The Global Farms Race: Land Grabs, Agricultural Investment, and the Scramble for Food Security,edited by Michael Kugelman and Susan L. Levenstein (Island Press, 2012)

- The Land Grabbers: The New Fight over Who Owns the Earth by Fred Pearce (Beacon Press, 2012)

- Rising Global Interest in Farmland: Can It Yield Sustainable and Equitable Benefits? by Klaus Deininger and Derek Byerlee (World Bank, 2011)

Links to data and additional resources may be found at Earth Policy Institute,www.earth-policy.org.

Will Foreign Land Grabbers Spark Local Revolts?

Land acquisitions, whether to produce food, biofuels, or other crops, raise questions about who will benefit. Even if some of these projects can dramatically boost land productivity, will local people gain from this? When virtually all the inputs—the farm equipment, the fertilizer, the pesticides, the seeds—are brought in from abroad and all the output is shipped out of the country, this contributes little to the local economy and nothing to the local food supply. These land grabs are benefiting the rich at the expense of the poor.

One of the most difficult variables to evaluate is political stability in the countries where land acquisitions are occurring. If opposition political parties come into office, they may cancel the agreements, arguing that they were secretly negotiated without public participation or support. Land acquisitions in South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, both among the top failing states, are particularly risky. Few things are more likely to fuel insurgencies than taking land away from people. Agricultural equipment is easily sabotaged. If ripe fields of grain are torched, they burn quickly.

In Ethiopia, local opposition to land grabs appears to be escalating from protest to violence. In late April 2012, gunmen in the Gambella region attacked workers on land acquired by Saudi billionaire Mohammed al-Amoudi for rice production. They reportedly killed five workers and wounded nine others. Al-Amoudi’s firm Saudi Star Agricultural Development was growing rice on just 860 acres of its 24,700-acre lease as of mid-2012, but it intends eventually to obtain another 716,000 acres in the region, with much of the rice harvest to be exported to Saudi Arabia.

Formulating Strategies for Global Food Security

The World Bank, working with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and other related agencies, has formulated a set of principles governing land acquisitions. These guiding principles are well conceived, but unfortunately, as critics like GRAIN point out, there is no mechanism to enforce them. The Bank does not seem willing to challenge the basic argument of those acquiring land, who continue to insist that it will benefit the people who live in the host countries.

Land acquisitions are being fundamentally challenged by a coalition of more than one hundred NGOs, some national and others international. These groups argue that the world does not need big corporations bringing large-scale, heavily mechanized, capital-intensive agriculture into developing countries. Instead, these countries need international support for local village-level farming centered on labor-intensive family farms that produce for local and regional markets and that create desperately needed jobs.

One important strategy would be to improve information collection on these international deals. A highly anticipated effort to compile information on large-scale land acquisitions, called the Land Matrix, was launched in April 2012. Its goal is to make data and descriptions of verified foreign land deals more accessible to research organizations, academics, and the general public. Unfortunately, while the project launch generated heavy media coverage, it soon became clear that the database had some of the same drawbacks as previous attempts. For example, certain large deals known for some time to have been canceled were still listed. The Land Matrix is an ongoing effort, accepting user feedback and submissions of new land acquisition examples, so it may prove a valuable tool as it is improved.

Energy policies could also have a great impact on ensuring food security. For instance, canceling biofuel mandates could quickly lower food prices by avoiding the massive conversion of food into fuel for cars.

It is becoming increasingly clear that future food security is integral to the future of global security as it is more broadly defined. As land and water become scarce, as the earth’s temperature rises, and as world food security deteriorates, a dangerous geopolitics of food scarcity is emerging. The conditions giving rise to this have been in the making for several decades, but the situation has come into sharp focus only in the last few years. The land acquisitions discussed here are an integral part of a global power struggle for control of the earth’s land and water resources.

About the Author

Lester R. Brown is president of Earth Policy Institute (www.earth-policy.org), a nonprofit, interdisciplinary research organization based in Washington, D.C.

This article is adapted with permission from his latest book, Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity (W. W. Norton & Company, 2012).

'곳간 > 해외자료' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 아프리카는 필요한 식량을 생산할 수 있다 (0) | 2013.01.16 |

|---|---|

| 도시를 먹여살리기: 도시 식량계획의 과제 (0) | 2013.01.07 |

| 유전자조작 옥수수밭의 섬뜩한 고요 (0) | 2013.01.03 |

| 유기농 텃밭이 건강이 아니라 환경에 훨씬 좋다 (0) | 2012.12.31 |

| 비만에 대한 보조금을 중단하자 (0) | 2012.12.31 |

A representative of Amundi Asset Management, Europe's third largest asset manager, explained to GRAIN that there is no definition of sustainable or responsible investing, at least not in the European Union.

A representative of Amundi Asset Management, Europe's third largest asset manager, explained to GRAIN that there is no definition of sustainable or responsible investing, at least not in the European Union. A lot of the current urge to regulate these deals boils down to words, specifically with the intent to differentiate "land grabs" from "investment" so as to establish not just the legality of these largescale land deals but a legitimacy as well. "A lot of our signatories don't understand the talk about land grabbing," one representative of UN PRI told us.

A lot of the current urge to regulate these deals boils down to words, specifically with the intent to differentiate "land grabs" from "investment" so as to establish not just the legality of these largescale land deals but a legitimacy as well. "A lot of our signatories don't understand the talk about land grabbing," one representative of UN PRI told us.